Culture seem like a good entry point into discussing the Babylon symbol as it's used in reggae. After all, they have NINE songs with Babylon in the title, and plenty more that contain Babylon deep within their grooves and words. In reggae, the Babylon symbol is always present, if only between the lines, and its meaning is pretty consistent--it's the system that's opposed to the will of Jah, and that keeps Jah's people (the Rastafari) from fully experiencing the divine life. Reggae is more nuanced when it asks the question, "Given its existence, what do we do about Babylon?" Joseph Hill, Culture's head honcho and chief lyricist, railed against the symbol in various ways, so Culture's stuff can serve as a lens through which to view the rest of reggae's "Babylon" symbology. It's not an exhaustive lens, but a useful one nonetheless.

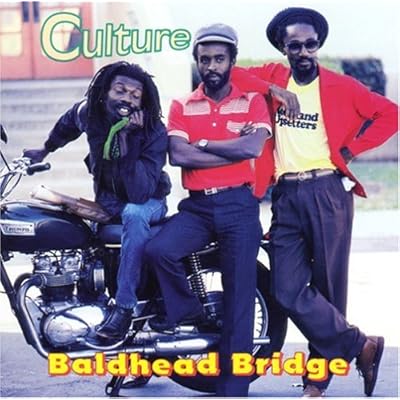

Their earliest Babylon song (going just by songs with "Babylon" in the title) was 1978's "So Long Babylon a Fool I (and I)", from the album Baldhead Bridge. To my ears, it's also their best--a slow elegy based on the older Nyabinghi drumming style, with some gentle horn and organ lines drifting along. (Nyabinghi drumming is built around three drums: the low Thunder, hitting on one and three; the mid-ranged Funde, sounding like a heartbeat; and the high Repeater, the song's lead instrument, improvising throughout. You can hear 'em all in this song! More familiar reggae beats and instrumentation grew out of this configuration.)

Lyrically, "So Long" has an ambiguous double-meaning. Sometimes Hill uses the title phrase to mean "farewell, auf wiedersehen, adieu"; sometimes he means, "MAN, we've been stuck in Babylon a long time!" He'd echo this theme of leaving in 2000's "Nah Stay Inna Babylon," and the "leave Babylon" strategy has been operative since the time of Marcus Garvey's Black Star Line (or since Israel's exile, depending how far back you wanna go). So there's one option.

Another option, also considered by Culture, is to "chant Babylon down." They advocate this move in 1997's not-so-ambiguously-titled "Chant Down Babylon," and also 1979's "Blood Inna Babylon." Note that they never advocate direct violence, and indeed I can't think of any reggae songs that do, though I'm sure they're out there. (Leave your requests and dedications in the comments, please!) Instead, Rastas tend to go for non-violent options. "Chanting down" is popular, and recalls Joshua circling the walled city of Jericho (though of course Joshua also proved to be a non-non-violent genocidal maniac). The chanting can also refer to calling down curses upon Babylon, as in "Blood": "I hail if Babylon kills one more Rastaman, I say / The sun will stop from shining / The grass will stop from growing." So ending Babylon is something we do, but we do it through Jah's hand.

If those don't suit ya, you can always simply MOCK Babylon. This seemed to be Hill's M.O. in the '80s, with 1980's "Babylon Can't Study" (...the Rastaman because he's bigger than Babylon) and 1982's "Babylon's Big Dog." Here's an interview with Hill that explains the inspiration for the latter tune:

“Well 'Babylon Big Dog' is a song created from the

unnecessary worries that babylon gives me. It's like I

was coming from a place in Jamaica called James

Mountain, in a very old car belonging to one of my

brethen called brother Honey... Instead of coming in, in peace, there was a

murder somewhere down the road. And then we realised

that Babylon [THE MAN] and his big dog [A COP] was there. As we pass

through, babylon tried to catch us, but this old car

was modified, and was too fast for them... So while we was

chasing away from babylon, I just start singing the

song and brother Honey crouch over the steering wheel

and start pushing the old car down," Joe laughs again.

"And they never catch us. So it really means it was

making me feel more victorious making the song triumph

over them."

And then sometimes you can simply ride it out. I'm thinking of '96's "Down In Babylon," which isn't so much about Babylon itself, as it is a lament for any sort of stable resistance to Babylon. Around a plaintive trombone solo, Hill asks, "Where are all the Rastamen who used to teach human rights and stand upright and lead and feed our nation?" [I paraphrase.] This presupposes that we're staying in Babylon, at least for the time being, and are organizing systems of our own to help bring about a society that Jah would like better.

(I'm too lazy to link to all these, but you know how to use Youtube.)

There may be other answers to the question, "What do we do about Babylon?" These four are certainly not mutually exclusive, but they also indicate that reggae answers its fundamental question more symbolically than politically. I may be wrong, but I'm not sure any reggae since Bob Marley has had measurable political effects. But that's not to say the situation's hopeless, that a symbol can't make a difference.

For one thing, the ideas of "leaving Babylon" and "chanting down Babylon" can empower individuals to change their everyday lives, even if it only means getting through the day a little happier. And for another thing, these symbols aren't just PREscriptive, they're also DEscriptive. Trevor McNaughton of the Melodians told me a couple years ago, "Babylon fall every day, man." You see this in every act of justice, whether it's one person sitting down to a meal with a homeless guy, or the SEC fining archenemies-of-the-people Goldman Sachs. God's/Jah's Kingdom breaks in where it will, and we do what we can to hasten it.

And in the meantime, Joseph Hill would advise, we can make fun of Babylon as we ride it out.

No comments:

Post a Comment