I keep wanting to ascribe all these naturalistic metaphors to Henry Threadgill's Zooid. And not just zooids! Thickets. Copses of trees. I kid you not, there was a moment during the first song, when Threadgill started playing his flute in the midst of his band's impeccably pointed counterpoint, when I thought I was watching Stan Brakhage's art house classic The Wold Shadow, which, if you haven't seen it, is a silent three minute look at a clearing in a forest that is gradually overtaken by paint applied directly and liberally to the film stock itself. It's meant to represent The Spirit of the Forest, I believe. Whatever, it's strange and beautiful. And Zooid were strange and beautiful. Just as colonies of zooids are strange and possibly beautiful, if you consider them in the right frame of mind, preferably after having read some profound literature re G-d's residence within all, even those things that look like giant spongy goiters.

My main man KGY thinks each Zoooid plays an individual riff or theme for an unspecified length of time, leading to unpredictable aleatoric structures that nonetheless avoid the stink of pure unbridled happenstance. (He described it so much better.) Then they switch to a different riff, but not at the same time, so what you've got is a constantly shifting web of unified sound. The drummer is in the groove, or "pocket," swinging like a gigantic bryozoan sucking the life out of an eel held by a curious child on holiday at the lake, trying to impress his little-seen cousins with his sense of heroic derring-do, because remember, bryozoans are poisonous if you release the wrong juices from their innards, although "innards" is a relative term because we're really talking about a bunch of little organisms stuck together in an apparently homogenous colony for the benefit of all, so whose "innards" get to be "poisonous"? -- I guess what I'm driving at is this: I don't know how bryozoa work, and I dunno how Zooid work, but they work unlike any band I've heard.

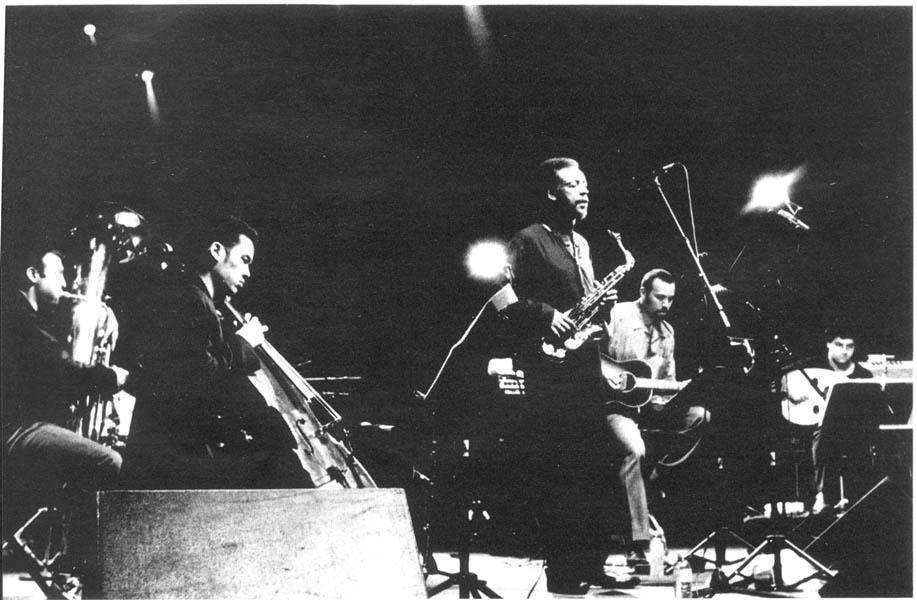

Delicate! -- but with the ability to build to a hard-charging unison riff with wild sax solo, in a way that doesn't seem forced at all. Everything they do has been calibrated to present the illusion of freedom, the freedom of nature, which is also an illusion -- you and I are governed by unchanging laws, buckaroo! Without overstating my case (which'd sound something like "Zooid get to the heart of the Free Will Vs. Determinism argument more surely than anyone since Lost"), I can tell you that Zooid sound premeditated and seat-of-their-pants all at once, which, when you think about it, is what most excellent bands and performers are striving for. Isn't that the goal of a Bach prelude -- to make it sound extemporized and perfect all at once? Wasn't that the goal of Weezer's Pinkerton -- to make it sound like Rivers's brain could fly apart at any moment, while leaving that impression marked indelibly on listeners' brains through its use of perfect songcraft? Isn't that what the Stones, the Stooges, Everclear hit over and over? And so! Threadgill has hit upon his own solution, which involves notated counterpoint (we don't know exactly how it's notated), solos by the flute the sax the trombone the cello and the EXTREMELY clean guitar, and an unending but everchanging groove laid down by everybody who's not soloing. Except Threadgill. Threadgill spent large portions of the show sitting down and beaming at the exquisite chaos he'd orchestrated. Then he'd get up and play his flute or his sax, and his lyricism or fire (respectively) was the paint of the Wold Shadow that put us, the listeners, directly inside the copse or the thicket or the goiterous poison blob. As I told the KGY after Song #1, I could've listened to these guys do their thing all night.

No comments:

Post a Comment